Many people have been protesting the election and inauguration of Donald Trump to the Presidency. Some of these protests have been accompanied with attacks on innocent people and destruction of private property, including breaking windows, looting businesses, and setting cars on fire. Some of these anarchists have sought to justify this destruction by claiming their actions were no different than early Americans, much like the Boston Tea Party (see picture). But such a comparison reveals their ignorance of America history. Let’s look at what caused the Boston Tea Party.

The Boston Tea Party

In 1765 King George III and Parliament passed the Stamp Act as a means to raise money from the American colonists to help pay for the French and Indian War. While the colonists were glad to pay for their defense, the Stamp Act imposed taxes upon them without the approval of their elected governing officials. The English government had never before imposed taxes upon the colonists without their consent.

The colonists were men of principle. One foundational Biblical idea upon which they lived and built America was the principle of property. They understood God gives individuals the right to own and govern property so they can fulfill His purposes on earth. They knew that if anyone could take their property without their consent, then they would not really own any property. They believed a primary purpose of government was to protect citizens’ property, but if their government plundered their property instead of protecting it, then it was their duty to act.[1]

Many of the colonies’ elected officials resisted the King’s unjust attempt to undermine their God-given rights. As a result, the Stamp Act was repealed. However, the belief of the English government to tax the colonies without their consent continued with the Townsend Act in 1767 and the Tea Act in 1773. With a tax on tea, the colonists refused to buy English tea and so it began to pile up in warehouses in England. Merchants petitioned the Parliament to do something. Parliament’s response was to vote to subsidize the tea and make it cheap, thinking the colonists would then buy it. Benjamin Franklin said:

They have no idea that any people can act from any other principle but that of interest; and they believe that three pence on a pound of tea, of which one does not perhaps drink ten pounds in a year, is sufficient to overcome all the patriotism of an American.[2]

Unfortunately, this may be enough to overcome the patriotism of many Americans today, though thankfully not then. The colonists were motivated by principles, not money. The attempt of England to tax them without their consent violated the principle of property. The Americans refused to buy the tea even though it was cheap.

When the King decided to send the tea and make the colonists purchase it, patriots in the major shipping ports held town meetings to decide what to do when the tea arrived. When the ships arrived in Boston, the patriots put a guard at the docks to prevent the tea from being unloaded. Almost 7000 people gathered at the Old South Meeting House to hear from Mr. Rotch, the owner of the ships. He explained that if he attempted to sail from Boston without unloading the tea, his life and business would be in danger, for the British said they would confiscate his ships unless the tea was unloaded by a certain date. The colonists decided, therefore, that in order to protect Mr. Rotch, they must accept the tea, but they would not have to drink it! By accepting the shipment they were agreeing to pay for it, but they would make a radical sacrifice in order to protest this injustice before the eyes of the world. Thus ensued the “Boston Tea Party.”

The men disguised themselves as Indians, not to implicate the Indians but to protect the identity of any one individual. They would all stand together as culprits. Historian Richard Frothingham records the incident:

The party in disguise…whooping like Indians, went on board the vessels, and, warning their officers and those of the customhouse to keep out of the way, unlaid the hatches, hoisted the chests of tea on deck, cut them open, and hove the tea overboard. They proved quiet and systematic workers. No one interfered with them. No other property was injured; no person was harmed; no tea was allowed to be carried away; and the silence of the crowd on shore was such that the breaking of the chests was distinctly heard by them. “The whole,” [Governor] Hutchinson wrote, “was done with very little tumult.”[3]

Unlike modern protestors who wantonly destroy property and claim it is in line with the American tradition to resist, the original tea party colonists were actually preserving private property rights (those of Mr. Rotch and the owners of the property on the ships, as well as of the colonists at large) while they protested the tyrannical action of the King. It was a masterful and principled response to a seemingly impossible situation.

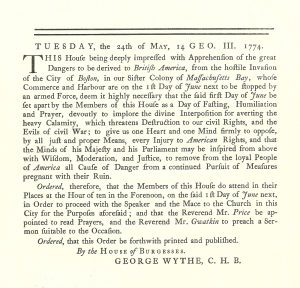

Boston Port Bill

When the King got word of what the colonists had done, you might say he was “tead off.” The English government responded by passing the Boston Port Bill, which closed the port of Boston and was intended to shut down all commerce on June 1st and starve the townspeople into submission. Committees of Correspondence spread the news by letter throughout all the colonies. The colonies began to respond. Massachusetts, Connecticut and Virginia called for days of fasting and prayer. Thomas Jefferson penned the resolve in Virginia “to implore the divine Interposition…to give us one Heart and one Mind firmly to oppose, by all just and proper Means, every injury to American Rights.”[4]

Frothingham writes of the day the Port Act went into effect:

The day was widely observed as a day of fasting and prayer. The manifestations of sympathy were general. Business was suspended. Bells were muffled, and tolled from morning to night; flags were kept at halfmast; streets were dressed in mourning; public buildings and shops were draped in black; large congregations filled the churches.

In Virginia the members of the House of Burgesses assembled at their place of meeting; went in procession, with the speaker at their head, to the church and listened to a discourse. “Never,” a lady wrote, “since my residence in Virginia have I seen so large a congregation as was this day assembled to hear divine service.” The preacher selected for his text the words: “be strong and of good courage, fear not, nor be afraid of them; for the Lord thy God, He it is that doth go with thee. He will not fail thee nor forsake thee.” “The people,” Jefferson says, “met generally, with anxiety and alarm in their countenances; and the effect of the day, through the whole colony, was like a shock of electricity, arousing every man and placing him erect and solidly on his centre.” These words describe the effect of the Port Act throughout the thirteen colonies.[5]

The colonies responded with material support as well, obtained, not by governmental decree but, more significantly, by individual action. A grassroots movement of zealous workers went door to door to gather patriotic offerings. These gifts were sent to Boston accompanied with letters of support. Out of the diversity of the colonies, a deep Christian unity was being revealed on a national level. John Adams spoke of the miraculous nature of this union: “Thirteen clocks were made to strike together, a perfection of mechanism which no artist had ever before effected.”[6]

Here we see an excellent historical example of the principle of Christian union. The external union of the colonies came about due to an internal unity of ideas and principles that had been sown in the hearts of the American people by the families and churches. Our national motto reflects this Christian union: E Pluribus Unum (one from the many).

The true story of the Boston Tea Party reveals that America was birthed by God-fearing, Biblically thinking people, and that Christianity provided the principles underlying the United States of America. If our schools taught American history accurately, modern liberals would much less likely attempt to justify their anarchy by saying they are only doing what our founders did. In fact, if we taught our true history, they might never have become the secular progressives they are today, but would, like our founders, become Biblically principled citizens who know how to live in liberty.

— To Learn more order America’s Providential History.

[1] To learn more about the principle of property see Mark Beliles and Stephen McDowell, America’s Providential History, Charlottesville: Providence Foundation, 1989, pp. 210-211, and Stephen McDowell, The Economy from a Biblical Perspective, Charlottesville: Providence Foundation, 2009, pp. 9-13.

[2] Verna Hall, The Christian History of the Constitution of the United States of America, San Francisco: Foundation of American Christian Education, 1980, p. 328.

[3] Beliles and McDowell, America’s Providential History, p. 131.

[4] Ibid., p. 131.

[5] Ibid, p. 131-132.

[6] The Patriots, Virginius Dabney, editor, New York: Atheneum, 1975, p. 7.

Comments

Thanks–excellent history. God please help us Christians to be salt and light.